Managing longevity risk

Living longer sounds ideal but how can you ensure your clients' finances will survive as long as they do?

Managing longevity risk for clients

Okinawa, Japan, is an interesting island, not just for its natural beauty but also for its people.

Okinawans could possibly be the world's most healthy elderly people. Far from being God's waiting room, towns and communities on the island are filled with people of pension age and over busy gardening, swimming, riding bicycles and taking part in daily outdoor exercises.

As a recent BBC report claimed, for every 100,000 inhabitants, Okinawa has 68 people aged 100 or over. This is more than three times the numbers found in US populations of the same size.

They are healthier, too: a high-carb, fresh diet of pesticide-free food, locally grown and sourced, has been credited by residents as giving them their life and health.

While the UK might be some way behind the health and longevity trends of Okinawa, there are lessons to learn about healthy lifestyles and a positive mindset as we move through our pensionhood into our later years.

But we are living longer - and in order to keep our lifestyle healthy and our mindset positive, we need to know our bank balances will be just as healthy.

With longevity comes the need for our pensions to stay the course with us. This means having a portfolio that can withstand maybe 20, 30 or even 40 years' worth of drawdowns, market shake-ups and various calls on the pot, such as funding later-life care - or that holiday to Okinawa.

This means the pension pot itself needs to have health checks by professional advisers. But how can advisers make sure their clients have not only accumulated enough in working life but also can have enough to live on for the rest of their lives once the client retires?

Add to this the recent lessons we have learned about sequencing risk and the market's tendency to react very badly to some black swan events, and it is clear the old totems of shifting from risk assets to bonds at retirement age, or taking a rule-of-thumb 4 per cent every year, will not cut it for all clients.

This report looks at the various issues with longevity planning, assessing the risks inherent with actuarial assumptions, sequencing risk, market drawdowns and how to make sure the pot does not run dry before it is no longer needed.

Simoney Kyriakou is editor of Financial Adviser

How can clients and advisers manage longevity risk?

When it comes to retirement planning, managing the unknown is the key challenge. And the greatest unknown is one's eventual date of death.

But with the responsibility put upon people to manage their retirement income following pension freedom changes, coupled with the increase in life expectancy, the management of the pensions pot has become even more critical.

Living too long, and outliving one’s retirement savings, is a risk. As Emma Byron, managing director of Legal & General Retail Retirement Income, comments: "Longevity is perhaps the most difficult part of the retirement puzzle. We’re living for longer and choosing more varied retirements than ever before.

"The notion of a ‘one and done’ solution is a strategy of the past and likely to prove ineffective in dealing with the variability that a longer retirement can bring."

And while in some cases life limiting conditions or behaviours – such as being a diabetes sufferer or smoking – will reduce the length of time someone can expect to live on average, it is impossible to be absolutely certain how long a client’s income will need to last for.

So how does one manage longevity risk?

There are two components to longevity risk, as explained in a research report in 2016 by City University’s Pensions Institute.

The first is the uncertainty over how long any particular pension scheme member is going to live after retirement. This is known as idiosyncratic longevity risk. Both individuals and schemes face idiosyncratic longevity risk.

The second is uncertainty over how long members of a particular age cohort are going to live after retirement. This is known as systematic longevity risk.

Only schemes face systematic longevity risk.

Pension schemes can reduce idiosyncratic longevity risk by pooling the risk among a large number of scheme members. Systematic longevity risk, however, cannot be reduced in this way: it needs to be hedged using a suitable hedging instrument.

The report added: “In order to help savers manage longevity risk, we need to understand both life expectancy and longevity risk and we begin with some observations on these.

“The main concern is that people who underestimate how long they are going to live face the possibility of running out of money before they die. This, in turn, suggests that idiosyncratic longevity risk is a risk that individual savers are not able – and should not be expected – to manage themselves."

Annuities

So, for most people the only realistic option to manage longevity risk is by arranging a lifetime annuity - offering a guaranteed income for life, Billy Burrows, retirement director at Better Retirement, says.

Tom Selby, senior analyst at AJ Bell, agrees. He says for people who want to pass the risks associated with their retirement, including longevity risk, to an insurer, annuities – while less popular than they used to be – could be a suitable option.

He says: “It is critical anyone considering going down this route discloses any medical conditions or lifestyle factors that could reduce their life expectancy to the insurance company to make sure they get the best rate possible.”

Flexibility

The introduction of Pension Freedoms in 2015 has meant that there is now a variety of options available to retirees. These include drawdown, annuities, cash withdrawal, and uncrystallised funds pension lump sums.

The Pension Policy Institute (PPI) says a combination of these can be used to balance flexibility against certainty (epitomised by an annuity).

Meanwhile, the Financial Conduct Authority's investment pathways are designed to protect unadvised consumers from taking particularly detrimental options, which is possible given the number of products available has increased.

Mr Selby suggests anyone choosing to go down the route of drawdown or ad-hoc lump sums (UFPLS), will need to consider a variety of risks, including longevity risk, when devising their retirement income plan.

When it comes to longevity risk, while large corporate pension schemes can purchase pure longevity insurance, for an individual, the only available solution is to use some of the pension pot to buy an annuity from an insurance company.

Life expectancy figures should only be used as a broad indicator; they can’t give you an accurate picture when planning a sustainable retirement income for your client.

Adrian Boulding, chief innovation officer at Spire Platform Solutions, says the greatest flexibility is retained if the annuity is purchased inside an income drawdown plan, rather than as a standalone insurance contract.

He adds: “This better reflects modern lifestyles, where people may 'un-retire' and return to work, or wish to use other assets outside of tax-favoured wrappers to cover living expenses in the early years of retirement.

“An annuity purchased inside an income drawdown plan will pay the monthly income gross, without any tax deduction, and pay it to the income drawdown plan’s cash account.”

From there the client can choose whether to withdraw it or whether to re-invest it, exactly the same as they would with any dividends received from income funds or shares in the income drawdown portfolio.

Ms Byron adds: "A guaranteed income to underpin a client’s portfolio and cover essential spending can largely mitigate longevity risk, while allowing you to invest your client’s other assets with more flexibility.

"It may be that combining a guaranteed income, such as an annuity, with a more flexible income suits some clients, while for those with a large proportion of their wealth tied up in their property, equity release may be more appropriate."

Blended approach

Clients can also try a blended approach; combining the option of an annuity with keeping money invested and taking income.

“Using some of your pot to secure an income from an insurer while retaining some flexibility and risk with the remaining portion,” Mr Selby adds.

“There are providers who offer to do this through a single packaged product, but in reality most clients should be able to achieve the same results simply by purchasing an annuity with one part of their fund and keeping the rest invested in a Sipp.

“Whichever approach someone takes, it is absolutely vital when buying an annuity to get the right product at the best possible rate, while in drawdown keeping costs as low as possible, reviewing your strategy regularly and managing your withdrawals sensibly should all be given due prominence.”

This is why regularly reviewing a portfolio is vital.

As a person ages their life expectancy does not reduce at the same rate that they are ageing. As explained by Evalue, if the joint life expectancy for a 65-year old couple today is 24.3 years, but by the time they are 80 (in 15 years’ time), their life expectancy is now 12.1 years, not 9.3 years – there is a an increase of almost three years to their expected age at death.

Ms Byron adds: "Life expectancy figures should only be used as a broad indicator; they can’t give you an accurate picture when planning a sustainable retirement income for your client. Even the most thorough of planning is not going to completely remove the risk of your client outliving their assets, particularly as there are so many factors at play."

She explains that, if people are asked to think about how long they might live, they tend to make assumptions based on the generations before them. Alternatively, they might base their thoughts on the average life expectancy data provided by the ONS calculator.

But, as she points out: "Neither of these account for socio-economic status, lifestyle, health or medical advancements. Planning to the average actually implies planning for a one-in-two chance of the client outliving their savings." This is why financial advice is so important.

For a retiree in drawdown, if they withdraw money to last their expected lifetime, then every passing year they have likely overspent and their remaining pot has to go further to meet the additional life they have “gained”. This is called mortality drag.

Jonathan Watts-Lay, director at Wealth at Work, says: "It is a very difficult balancing act, but the only way you can do the balancing is to ensure you do the annual reviews, because no one can predict the future.

"We know there are lots of variables and lots of unknowns; we don’t know what the market will do or when [a person] will die. All you can do is manage your portfolio around what you know today and make sure you are regularly reviewing it."

ima.jacksonobot@ft.com

Via Pexels.com

Via Pexels.com

Oleg Magni via Pexels

Oleg Magni via Pexels

How to overcome sequencing risk in portfolios

Sequence of returns risk is a challenge, particularly right now with markets volatile in response to the impact of Covid-19.

The danger is that the timing of withdrawals from a retirement account could have a negative impact on the overall rate of return available to the investor.

We have witnessed the first bear market since the pension freedoms were introduced in 2015 as a result of Covid-19, with people relying on their pension fund to produce an income in retirement, being perhaps the most affected by such sudden market falls.

As Jon Scannell, distribution director for Legal & General Retail Retirement Income puts it: "We’re navigating a particularly unusual time right now but market volatility is inevitable."

While he says we all know to avoid falling into the trap of trying to time the markets, many people may be facing the problem of the market's own timing working against them.

He adds: "Those approaching retirement are likely to be in more secure investments and, therefore, better protected from volatility. However, for recent retirees the timing of withdrawals and level of drawdown at the end matters a lot."

So, sequence risk is especially damaging to clients drawing a retirement income, as there really is no way back if a portfolio is depleted by having to sell assets at low prices.

Hence, it really does need to be part of the conversation that advisers have with clients, to avoid it rearing its head later as an unwelcome surprise.

Mr Scannell adds: "The impact of ‘pound-cost ravaging’ early on in retirement can have a significant impact on the value of their assets and can, ultimately, leave them having to make difficult decisions about reducing or stopping their withdrawals to avoid eroding their pension savings.

"While you may have had these conversations upfront with your clients, it’s likely a difficult conversation at the point of having to make these changes. Having a level of guaranteed income to secure essential spend in retirement can, ultimately, provide clients with greater security and flexibility."

The cash buffer

Historically, people have used cash buffers as a way to reduce sequence risk, Adrian Boulding, chief innovation officer at Spire Platform Solutions, explains.

If the client’s portfolio contains enough cash to meet, say, the next three years of required pension, then asset sales can be deferred during the times when markets are low.

But the problem with this is the opportunity cost, as with Bank of England Base Rate stuck at just 0.1 per cent, cash in a portfolio is sitting idle earning only a nugatory return.

Also, the FCA is getting increasingly unhappy at large amounts of cash held in portfolios and increasingly asking whether that really is in the clients’ best interests.

Mr Boulding suggests one solution may be to incorporate an annuity into the portfolio.

He adds: “An annuity behaves very much like a corporate bond, and unsurprisingly, insurers themselves often invest the premium they receive for selling an annuity into corporate bonds.

“In terms of portfolio construction, the annuity should be seen as a replacement for some of the corporate bonds that the adviser or discretionary fund manager would otherwise have recommended.

“When the client is shown how two portfolios project forward stochastically – one containing corporate bonds and the other with the bonds hollowed out and replaced with annuity – they will see how this re-construction has de-risked the portfolio. For the same pension withdrawals, the risk of running out is reduced and the projected portfolio values in later life are higher.”

Where cash buffers negate sequence risk at a high opportunity cost to clients, using an annuity neatly passes that sequencing risk across to an insurer.

Anyone making a withdrawal from their pension while also suffering a hit on their underlying investments will struggle to make the money back, meaning they may have to reduce their income now or face the prospect of running out of money sooner than expected.

There are various strategies in conjunction with regular reviews investors can use to mitigate the risk of sequencing risk or ‘pound-cost ravaging.

The difference in retirement outcomes as a result of the timing of negative investment returns can be significant, Tom Selby, senior analyst at AJ Bell, says.

He gives an example of where someone taking a 5 per cent inflation-adjusted income from their fund who suffered a 20 per cent hit in their first year in drawdown could see their pension pot run out after 18 years – three years sooner than if they suffered the hit 10 years into retirement.

By contrast, someone who enjoys 4 per cent growth throughout their retirement could take the same income for 25 years.

To put this into context, while on average life expectancy at 65 is 18.6 years for men and 21 years for women, a man has a 1 in 4 chance of living another 27 years, while a woman has a 1 in 4 chance of living another 29 years.

Mr Selby stresses: “This is exactly why drawdown clients who are taking an income from their capital need to build a sustainable withdrawal strategy and review that strategy regularly.

“There are various strategies in conjunction with regular reviews investors can use to mitigate the risk of sequencing risk or ‘pound-cost ravaging’.

“If clients have any other cash investments they might consider drawing on these first rather than selling down capital at a low point in the market to fund their retirement spending.

"This will give their underlying investments better opportunity to recover value after a market dip.”

Using just the ‘natural income’ a client’s investments produce can also mitigate the risk of pound-cost ravaging, although they may have to accept a variable income as a result.

This would have been particularly difficult in 2020, however, with many companies slashing dividends or stopping the payments altogether.

Why sequencing risk is a problem for decumulation investors

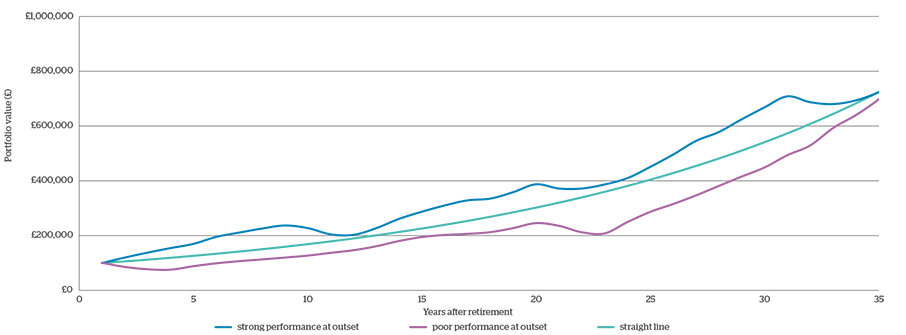

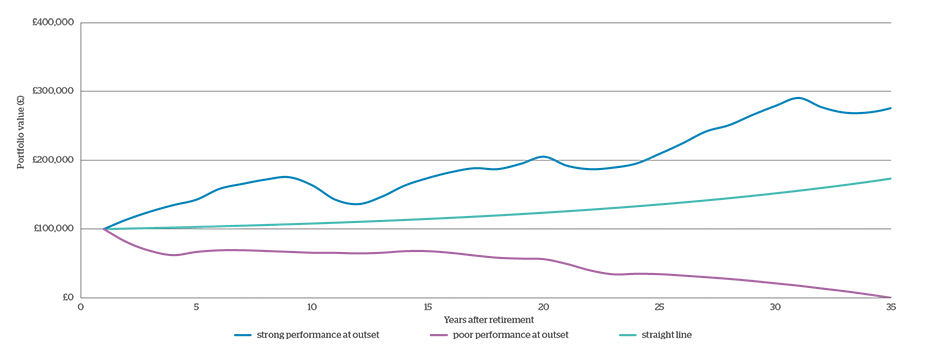

Chart 1 and chart 2 show examples of a £100,000 portfolio across a 35-year timeframe.

Chart 1: No withdrawals

The reason that the ‘poor performance at outset’ line recovers over time is because when markets are weak, the portfolio is able to reinvest at lower prices (because no withdrawals are being made in this example).

Portfolio value therefore has the ability to recover and return to the long-term average over time.

Source: Brooks Macdonald

Chart 2: £5,000 per year withdrawal

If the portfolio enjoys good performance at outset, portfolio growth is able to overcome the amount of income being withdrawn, and portfolio value increases over 35 years.

If the portfolio suffers from weak returns at the outset and £5,000 of income has been withdrawn every year, the portfolio never has enough time to recover those initial losses

Source: Brooks Macdonald

According to Billy Burrows, retirement director at Better Retirement, there are two schools of thought; the first is to invest for the long term and reduce income withdrawals if there is a market crash and increase income if there is higher than expected growth; the second, is to manage the sequence of returns risk by adopting a variation on the three bucket approach.

Mr Burrows says: “That is cash or very low risk funds to pay income for 2 to 3 years, a medium risk fund and a longer term growth fund. The cash fund should then be regularly topped up from the other funds depending on market conditions.”

Although in theory this is fine, Mr Burrows explains in practice it is very difficult to know when to sell units in the growth fund to top up the cash fund.

"Personally, I think anybody who is not trying to manage sequence of returns risk, no matter how basic, is asking for trouble,” he adds.

Covid-19 has had a limited effect on funds which employ a lifestyling strategy, one which automatically switches pension savings into another fund which may be of lower risk.

Taking income

Caroline Cochrane, a director at Crandles and Co, says one can avoid the sequence risk by taking income without having to sell assets.

Annuities are not affected by sequencing risk as there is no investment element to the contract.

She suggests the following:

1) An individual could retain a sum in cash, often around two years income, which is drawn on for monthly payments and when markets stabilise sell another portion of funds to top up the cash account within the pension.

2) Or, depending on the income required and the assets within, one could draw the natural income from the pension. This would leave the capital invested but relies upon the variable income generated from dividends, interest payments and such like.

She adds: “Of course one must balance the pros and cons of all options and so a combination of all would likely be the best option.”

If a client has no capacity for loss then a lifetime annuity is the best option and this provides a guarantee for the rest of their lives, Ms Cochrane explains.

She adds: “If a client has low income needs and does not require a specific amount each month then the natural income from assets would be most appropriate.”

The lower the attitude to risk the lower likely income generated and this must be accounted for.

Ms Cochrane says: “Having funds in cash will provide a known income, for as long as the cash lasts and those with higher capacity for loss and higher risk may consider this the most suitable for them.

“For those with a higher risk appetite one could always invest with no buffer against sequencing risk as they may consider the advantage of all funds being invested more attractive than the consequences of sequencing risk in a falling market.”

Patrick Ingram, head of strategic partnerships at Parmenion, says reducing exposure to uncertainty can be managed by setting an appropriate balance or ratio between a client's level of guaranteed income with their minimum income and target income levels.

He adds: "If you can practically flex down from target withdrawals to minimum acceptable withdrawal levels you will be able significantly to avoid the impact of sequence of return risks and if you don’t have an exposure to potential falls in income because your secure income levels are high, the challenge is significantly offset."

ima.jacksonobot@ft.com

How to avoid behavioural biases in longevity planning

The world has moved on and clients no longer need to choose between annuity and drawdown.

Many clients are opting for a blended approach, to get the promise of an annuity to pay for bills, and the flexibility of drawdown, but ultimately their financial decisions will involve trade-offs.

And, at the risk of stating the obvious, managing this trade-off between security and flexibility is one of the key roles of a financial adviser.

But by understanding a client’s needs, priorities and appetite for risk, a good adviser can help design a suitable, sustainable retirement income strategy.

Adrian Boulding, chief innovation officer at Spire Platform Solutions, says this flexibility can help those who have a natural aversion to making large purchases.

The annuity purchase can be made in slices, with an initial allocation to annuity being topped up with further purchases in the future, perhaps as capital gains are crystallised.

Mr Boulding adds that spreading the purchase is not just 'good investment sense', but by avoiding timing risk, it also helps with what may be a natural behavioural aversion to making large purchases.

By having a secure, reliable income at its core, advisers can take suitable risk elsewhere with other assets.

Some annuities today now come with a surrender facility, so if client circumstances change in an unexpected way, the annuity transaction can be unwound.

That addresses another behavioural bias - namely, the reluctance to make irreversible decisions.

Mr Boulding says another behavioural bias that needs to be addressed is loss aversion, which can be addressed by buying an annuity with a high death benefit.

He adds: “Nobody wants to be the person that buys an annuity and dies shortly afterwards, leaving their children thinking “if only Dad hadn’t bought that”.

“But equally nobody wants to buy such a comprehensive death benefit that it seriously reduces the annuity rate, hitting the regular monthly income.

"This apparent dilemma can be resolved by buying an annuity with a high death benefit in its early years, but a death benefit that tapers away over time. This way the risk of serious loss can be covered without giving up too much of the valuable income.”

Part of an adviser’s job is therefore bringing to life the risks ploughing on with an unsustainable income strategy could have to a client in the future.

Money today or money tomorrow?

According to Tom Selby, a senior analyst at AJ Bell, an obvious behavioural bias to navigate will be hyperbolic discounting – the fact humans generally value money today over money tomorrow.

This in turn could lead to clients wanting to withdraw higher amounts of cash in the early years of retirement without having due regard to the longer-term sustainability of their plan.

Mr Selby adds: “Part of an adviser’s job is therefore bringing to life the risks ploughing on with an unsustainable income strategy could have to a client in the future, and helping them balance this against a desire to enjoy the lifestyle they want today.”

Billy Burrows, retirement director at Better Retirement, says the more effort put into cash flow modelling the easier it is to decide what is the best trade-off.

He suggests a 50/50 split between annuities and drawdown may be better than a single product solution, although it is not a “very sophisticated” solution.

Mr Burrows adds: “In my view it is better to view the trade-off as being dynamic, for example, de-risking by arranging annuities when circumstances and market conditions dictate.

“Good retirement advice involves taking into account both technical and behavioural factors.

"For instance as people get older the case for annuities gets stronger because there is more benefit from the mortality cross subsidy. At the same time, emotionally and behaviourally, people are more concerned about their peace of mind and financial security.”

Crucially, people need to be aware not just of their own mortality but their need for long-term care and the importance of making sure they have enough money in their pension pot to account for what could be a significant and sharp rise in expenditure to accommodate long-term care provision.

John Scannell, distribution director at Legal & General Retail Retirement Income, comments: "While we’re living longer, for many people this will, unfortunately, also mean a longer time in poor health. Although around one in five men, and one in three women over 65, will need residential care during their lifetime, there are a further group that will require some form of care or support in the home.

"So planning for expensive residential care that may not be required is not really the ask. Instead it is about the interrelationship between providing an adequate income, creating a legacy and funding for care if required.

"Balancing these three things, and continuing to review their financial plans with them on a regular basis, is critical. We believe the best way to manage this interrelationship is through layered retirement plans that meet their objectives. By having a secure, reliable income at its core, advisers can take suitable risk elsewhere with other assets."

ima.jacksonobot@ft.com

Creating a tailored plan can help overcome behavioural biases. Image: Kaboom pics via Pexels

Creating a tailored plan can help overcome behavioural biases. Image: Kaboom pics via Pexels

Naomi Bouhout via Pexels

Naomi Bouhout via Pexels

Skitterphoto via Pexels

Skitterphoto via Pexels

Getting the right balance is critical. Image: Pixabay via Pexels

Getting the right balance is critical. Image: Pixabay via Pexels

Why balancing varying needs against the pension pot is vital

With longevity comes different needs and varying calls on the pension pot, which our forebears may not have had to consider.

For example, some families now rely on the older generation to help fund the youngest generation's educational or housing needs; other people who are enjoying good health later on in life are thinking more about taking the holidays of a lifetime they had always dreamed of while working.

Indeed, some clients have been very well paid all their lives and have sufficient funds to do everything, have a comfortable retirement, be able to afford long term care and still have funds to pass to their family, but this potentially will not happen for many clients.

In theory, according to Emma Byron, managing director for Legal & General Retail Retirement Income, people ought to be able to maintain a sustainable income in retirement, leave a legacy on death and fund care costs if required in the future.

In practice, trade-offs often have to be made. "Therefore the main priority for most will be to have enough income to enjoy a comfortable retirement."

But recent research from the Pension and Lifetime Savings Association has shown that for a ‘comfortable’ retirement, an individual would need approximately £33,000 per year (£47,500 for a couple).

‘Comfortable’ is defined as the ability to cover three weeks of holiday in Europe each year, two cars replaced every five years, £91 per week on food, up to £1,500 per person on clothing and personal expenses a year, and the opportunity to replace the kitchen or bathroom every 10 to 15 years.

She comments: "While it’s easy to imagine that those seeking financial advice are likely to be able to cover this amount from modest returns on their investment portfolio, even a £400,000 pot in drawdown, combined with a state pension of £18,221 per annum, may not provide enough for a ‘comfortable’ and sustainable income."

Care or home help needs

While mortality decreases due to medical advances, morbidity - the rate of disease in a population - increases, because people no longer die from certain conditions, instead they are spending more time with disabilities or in an unfavourable state.

So how can advisers help clients balance their retirement portfolio to allow for income while also keeping a capital sum invested to help pay for future needs such as care or leaving an inheritance.

The Pensions Policy Institute says to be able to retain the sums of money required to fund long-term care would only be available to those with large amounts of savings.

These individuals should consider personalised advice that considers the entirety of their financial situation including property and other financial savings.

They may want to optimise their tax situation as holding a large amount in a pension that needs to be withdrawn at once could present a hefty tax bill as it will all be treated as income.

Passing on an inheritance

For many people at retirement age and above passing money to loved ones will be a primary consideration.

Rules introduced in 2016 mean that Sipps are now extremely tax efficient on death, and can be passed on tax-free to nominated beneficiaries if the holder dies before age 75 and at their beneficiaries’ marginal rate of income tax if they die after 75.

Tom Selby, a senior analyst at AJ Bell, says because of this generous tax treatment, where passing money on to loved ones is a priority, it can often make sense for the pension to be among the last assets a client touches.

Mr Selby adds: “Although death might be certain (if unknown) for all clients, long-term care needs are much harder to predict and so tricky to plan for.

"There are insurance products available for those who want to insure against this risk – such as immediate needs annuities – but the market is relatively limited at the moment, in part because the care costs an individual might face are difficult for insurers to quantify.”

One option, if a client can afford to, is to earmark a portion of their pension pot for long-term care (if needed) and invest this in relatively low risk assets.

However, the trade-off here will be that a client might sacrifice the possibility of longer-term growth – particularly if their investment time horizon is 10 years or more.

Mr Selby says: "This is one area where good quality advice involving regular client reviews can be of crucial importance." He adds this needs continual oversight, especially if care needs have to be factored into the plan.

Other income needs

But for Caroline Cochrane, director at Crandles and Co explains, pensions were not designed to be passed to the next generation and clients should be aware that although pension funds can be passed as pensions to their children and others, the primary reason for a pension is to provide an income in retirement.

There are still bills to be paid, holidays to be taken, hobbies to be enjoyed, gardens to be tended to and food to be eaten.

Not for nothing have successive governments pandered to the 'grey pound', seeing the potential spending power of a generation of people who want to spend retirement doing the things they enjoy.

Home improvements, also, are a common reason why pension clients often opt to take their 25 per cent tax-free cash upfront, so they can create a living space in their homes, where they foresee themselves spending a lot more time than while they were working.

However, upgrades and maintenance itself also needs to be considered - and this will end up being a call on the income from the portfolio.

Therefore, Ms Cochrane says clients passing these funds to the next generation should consider this as a bonus and not as part of retirement planning unless there are very substantial funds.

The flexibility of pensions means that if the client requires care then income payments from the pension can increase to meet some or all of these costs - although not all powers of attorney allow changes to be made to a pension plan.

Additional pension payments will be taxed, so if a client has funds which are not pension then they could purchase an immediate needs annuity and if paid to a care home has no tax charge on income.

As a result, Ms Cochrane believes equity release is increasingly being signposted as an option for funding needs, such as long-term care or significant home improvements.

She adds: “If a client’s income and pension funds are not sufficient to provide for them for their lifetime then one should consider the option of equity release on the family home.

“Often this is the largest asset but is not accessible unless one sells or arranges equity release. Equity release can be flexible, not only providing a lump sum if required but also a regular income.”

Trade-offs

Essentially, as Ms Byron comments, humans are "naturally drawn to the here and now. When considering trade-offs, present bias refers to the tendency to favour the pay offs of something happening now vs in the future.

"That means clients are likely to think in shorter time horizons, finding it difficult to fully engage with the more holistic planning conversations you have together. Trying to use their shorter term goals as a way of showing the longer term impacts may be one way to highlight this bias."

This is why she advocates discussing their basic income requirements, as shown by the PLSA, and developing plans that secure this amount can provide added flexibility for the rest of a client’s assets.

Cashflow planning

Billy Burrows, retirement director at Better Retirement, says a detailed cash flow will help to identify the amount of income required in the future and a good adviser will model a number of scenarios including the need for expensive health care in later life.

Adrian Boulding, chief innovation officer at Spire Platform Solutions, agrees.

He says: “It’s really useful for clients to see their income needs planned out to an advanced age, say age 100. This cashflow approach can show how essential needs and lifestyle expenditure will change as age creeps up on us.

“And how the residual capital is projected to behave, so the client can feel reassured that those longer term aspirations such as inheritance, or home alterations are catered for.

“Incorporating an insured product that provides a guaranteed income for life into the portfolio de-risks these long term projections, as the client can see that essential bills will always be covered, in even scenarios that look at periods of poor investment returns.”

ima.jacksonobot@ft.com